The Deepwater Horizon spill was among the worst environmental disasters in history. Eleven platform workers lost their lives when the rig exploded on April 20, 2010. Over 4.9 million barrels of crude oil were released into the Gulf of Mexico, and many experts say that irreversible damage may have been done to the local environment.

In addition to these very tangible losses, however, BP’s poor communication in the wake of the disaster compounded their mistakes in myriad ways. It resulted in such damage to their brand that BP-branded gas stations throughout the country changed their name to avoid association.

There were many missed opportunities throughout the timeline of the crisis; times when BP could have shown leadership and compassion that would have helped them mend trust. Other organizations can learn from these errors to ensure that their planning and their reactions are better. Taking some time to examine specific mistakes can help reveal a number of specific lessons that other organizations can take if they are ever faced with a severe disaster.

“You know, I’d like my life back.”

CEO Tony Hayward proved early on that he did not understand the gravity of the situation. Hayward made a number of PR missteps, including making insensitive comments to reporters. Several days into the crisis, Hayward said, “There’s no one who wants this thing over more than I do. You know, I’d like my life back.” He was quick and harshly taken to task for making such a flip statement about his life when nearly a dozen employees had lost theirs.

This gaffe and others, such as appearing unrelatable while walking on the beach in Louisiana in a starched white shirt, showed that Hayward did not appreciate the very real impact the spill had on many in the area.

The lesson: Remember that it isn’t about you. No matter what happens, executives communicating with the press and the public need to remember to keep the focus on those injured, dead or harmed in some other way.

Cutting Budgets to the Bone

In the wake of the tragedy, it soon became apparent that BP had not planned properly for the safety of their workers or of the local environment. The company had also failed to plan for the health of its public perception. According to former BP executive Glenn DaGian, Hayward had slashed budgets for PR and government relations in an effort to cut costs. The result was an organization that was not ready to face the public.

The time to hire a crisis communications consultant is not in the hours after a tragedy. It is in the months and years before. Your crisis communications plan should include a list of possible disaster scenarios and how executives and other stakeholders should respond to each one. Public facing employees should be trained so that they know what words and actions can help and which are likely to cause further problems.

It should also have a list of people to contact as soon as possible in order to help communicate effectively with the public to save trust. DaGian, who is from the Louisiana coast, said that he immediately called old contacts at BP to offer his help. A highly damaging week passed before they took him up on his invitation and brought him to the coast to talk to fishermen and others worried about their jobs and their future.

The lesson: Crisis communications planning is not optional.

Walruses.

The release of BP’s disaster plan for Deepwater Horizon further damaged trust in the company and its ability to make its errors right. Mentions of wildlife that included walruses, sea lions, and seals (none of which live in the Gulf of Mexico) revealed that the details of the plan had not been created with Deepwater’s ecosystem in mind.

Additionally, the plan named a Japanese home shopping website as one of its primary equipment providers in the Gulf of Mexico region. Needless to say, the website did not stock equipment integral to contain a spill.

While safety and continuity plans are internal documents, organizations should assume that they will be made public in the event of a disaster. Plans should be made to fit specific contingencies appropriately and updated when needed to fit the latest knowledge about disaster mitigation. A quality plan doesn’t just ensure an appropriate response. It shows the public that your organization is competent, trustworthy and attentive.

The lesson: invest the time in a relevant and actionable plan for your most likely disasters.

A “Very, very modest” impact

A month after the oil spill, Hayward described the environmental impact of the Deepwater Horizon spill as likely to be “very, very modest.” This, however, proved to be far from true. Experts estimate that the spill was among the worst in history and that its impact on the local area would be indelible.

Additionally, the public soon learned that BP had significantly underestimated the flow rate of the damaged oil well. By their calculations, the well would have spilled under 1,000 barrels of oil per day. However, outside scientists found that the real flow rate could be as high as 60,000 barrels per day but was at least 35,000 barrels per day. BP’s lowball estimate, along with their refusal to amend it, came off as disingenuous to the public.

The lesson: be transparent and accurate. When the public uncovers lies, it destroys credibility.

“Small People.”

After a meeting with former President Barack Obama to discuss the impact of the spill, BP board Chairman Carl-Henric Svanberg said that he shared Obama’s compassion for the “small people” who lived and worked by the Gulf.

Svanberg’s wealth, paired with American connotations of class privilege, meant that the comment did not sit well with most who heard it. However, it is likely that there was no negative connotation intended in Svanberg’s words. In Svanberg’s native language, Swedish, the word “småfolket” has a positive and egalitarian connotation. However, since most Americans are not familiar with this aspect of Swedish language and culture, the meaning was lost in translation. As a result, it further drove perceptions that BP was uncaring.

The lesson: Understand the people and communities who are affected. Communicate using the sort of language that those most affected will use.

Don’t Forget Your Investors

In the months after the spill, BP’s stock price plummeted for what should seem to be obvious reasons.

However, in a statement from the company about the drop in value, BP said, “the company is not aware of any reason which justifies this share price movement.”

While the company was trying to convey that it could handle the costs of the oil spill clean-up, they instead seemed dismissive of the disaster. The trust of BP investors was irreparably harmed. To this day, BP shares have not regained the price levels they had before the spill.

The lesson: overconfidence does not win investors’ trust.

Putting Your Money Where Your Mouth Is

A month and a half after the beginning of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, BP launched a $50 million TV ad campaign. In this campaign, the company promised to restore the environment in the local area.

Barack Obama commented that the money should have been applied to actual clean up efforts and damage claims instead of promises.

Few in business can deny the importance of quality crisis communications and public relations efforts after a disaster. However, appearances matter. When the public feels that more effort is being put into saving face than in fixing the problem, the most expensive ad campaign in the world can’t fix that.

The lesson: Be careful about advertising. An effort to save face should match up with what the public knows of your efforts.

The Takeaway

Sometimes, disasters blindside us. In other cases, hindsight provides clear signals that one was about to occur. By learning from the errors of other companies, your enterprise can avoid costly disasters and recover from them more effectively.

Can we help you?

We’ve built the crisis management and rapid response process for all sorts of organizations around the world – and trained their executives to be effective crisis leaders and communicators for their organizations. Learn more about our approach to Crisis Management in our Ultimate Guide to Crisis Management.

Let us bring our expertise to your particular challenge. Contact us today at +1.612.235.6435 or via our contact form.

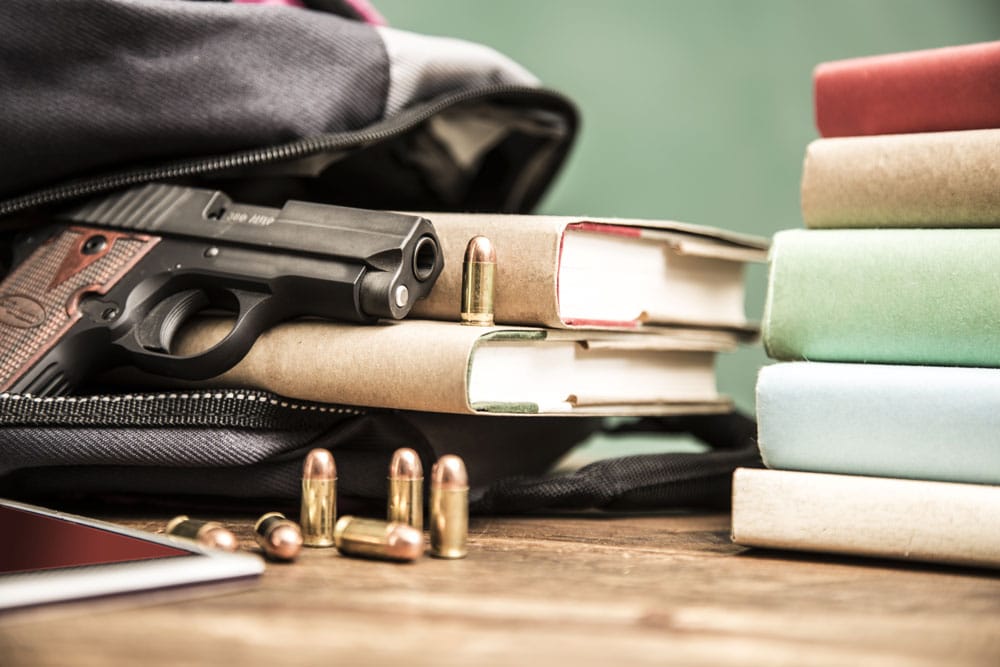

Diving into the Secret Service’s Report on School Threat Assessment Teams

Diving into the Secret Service’s Report on School Threat Assessment Teams